When a homicide detective in California’s Central Valley last year reopened the investigation into the unsolved killing of a bakery owner, she turned to an increasingly popular forensic tool credited with helping solve hundreds of cases across the United States and Canada in recent years.

The detective, Ashley Sanchez of the Kern County Sheriff’s Office, said she was confident she had evidence that could help identify a person whom she believes was involved in the gruesome 2010 death of Juanita Francisco, 49. But paying for the genetic genealogical work needed for that effort was not so straightforward, she said.

In the end, it was funded not by local taxpayers or a state or federal grant, but by a crowdsourced fundraiser.

That unusual funding source reflects what experts say is the often grim financial reality for many seeking to use the technique, which surged in popularity after the arrest of the “Golden State Killer” eight years ago and has been used to solve more than 1,600 cases in the U.S. and Canada, according to an ongoing tally updated earlier this year by a criminology professor at Douglas College in Canada.

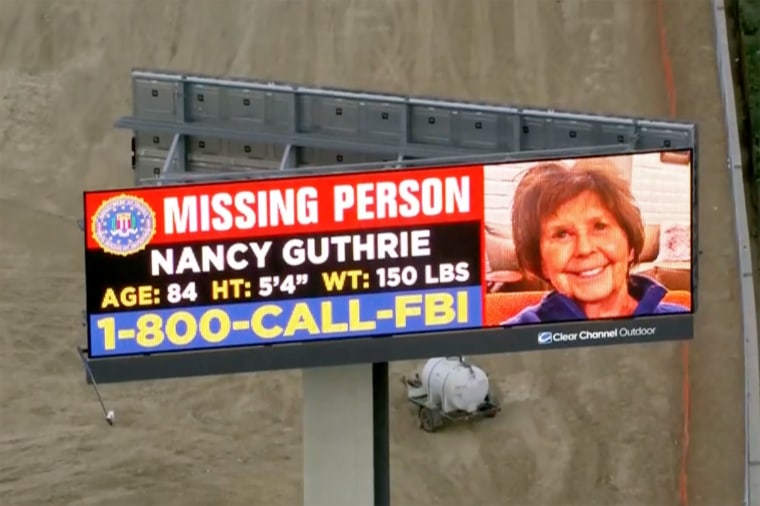

Authorities investigating the possible abduction of Nancy Guthrie are also exploring the possibility of using the method, which relies on traditional genealogical research and modern DNA analysis to unravel unsolved crimes and cases of unidentified human remains.

Some government grant funding is available, said David Gurney, director of the Investigative Genetic Genealogy Center at New Jersey’s Ramapo College, but the amount of money provided by the federal government and states “is not even scratching the surface.”

In many instances, that means crowdfunding has been the solution. Tracey Dowdeswell, the criminology professor in Canada, estimated that roughly 120 of the 1,600 cases in her database were crowdfunded, though she said that number is likely an undercount and she cautioned that many cases often have several sources of funding. Most are cases of unidentified remains, she said.

Dozens more cases listed on sites like DNA Doe Project, Moxxy Forensic Investigations or DNASolves — where Francisco’s funding drive was posted — have been successfully crowdfunded and not yet solved or posted and not yet funded.

“I think it is amazing that members of the public are willing to donate money to help solve these cases,” Gurney said. “But it’s not a sustainable criminal justice system.”

David Mittelman, CEO of Othram, the Texas-based DNA lab behind DNASolves, described that site as the destination for a subset of the company’s cases that “literally cannot be worked — not because there’s no evidence, not because there’s no interest, but because there’s no funding channel for them.”

To Gurney, the necessity of crowdfunding shows how little awareness there is that genetic genealogy could help clear the backlog of unsolved cases in the U.S. He cited federal data showing the method could potentially be used in hundreds of thousands of unsolved violent crimes and tens of thousands of unidentified remains cases.

“It’s going to be difficult to scale up this work to tackle the backlog of uncleared cases until there is more funding,” Dowdeswell said.

Just a handful of labs

Genetic genealogy relies on a few crucial components. Researchers need a DNA sample — and a profile — for the person they’re trying to identify. And they need to upload that profile to GEDMatch or FamilyTreeDNA, the consumer DNA databases that permit access for law enforcement purposes. That profile can then be used to develop a family tree to help pinpoint the source of the unidentified DNA.

Obtaining a suitable profile can be a daunting task, however, since the DNA samples needed to develop those profiles are often old and degraded, said Kendall Mills of Season of Justice, a nonprofit that fundraises for law enforcement agencies that need advanced DNA analysis but can’t afford it.

Only a handful of private labs in the U.S. — labs like Othram — are capable of doing the kind of work required to develop those profiles, Mills said.

“Typically, the private labs have access to more sensitive technology, newer technology,” she said. “They also have the ability to conduct a lot of research and development that our taxpayer-funded labs just don’t have the capacity for. But they come with a higher price tag.”

The consumer DNA databases provide researchers access for a fee of more than $1,000, Gurney said.

Some state and federal agencies are beginning to do the labor-intensive genealogy work that follows, Gurney said, but the vast majority of that research is done with assistance from a patchwork of nonprofit organizations, for-profit companies and at least one school — Ramapo.