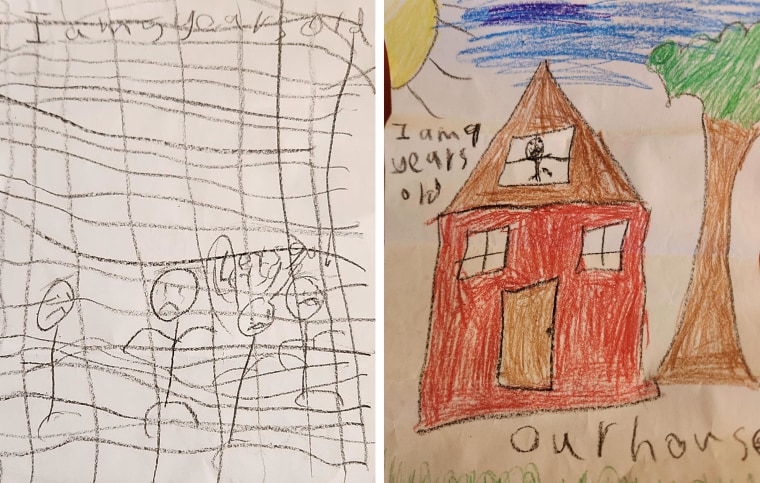

Before she arrived at the Dilley Immigration Processing Center last fall, Kelly Vargas said, her 6-year-old daughter was thriving. Maria loved school and spent her afternoons drawing and playing with her cat.

But Vargas said that within days of the family’s being detained and sent to the prisonlike facility in South Texas — where guards patrol the halls and the lights never turn off — her daughter began to unravel.

After years without accidents, Maria started wetting her pants and her bed. She cried through the night, asking when she and her parents would return to their apartment in New York. She begged to start breastfeeding again.

Vargas, who was deported to Colombia with her family in November after having spent nearly two months at Dilley, said she never imagined the United States could act so callously.

“How are they going to do this to a child?” Vargas told NBC News, speaking in Spanish. “How could this happen here?”

Accounts from detained families, their lawyers and court filings describe the federal detention center in Dilley as a place where hundreds of children languish as they’re served contaminated food, receive little education and struggle to obtain basic medical care.

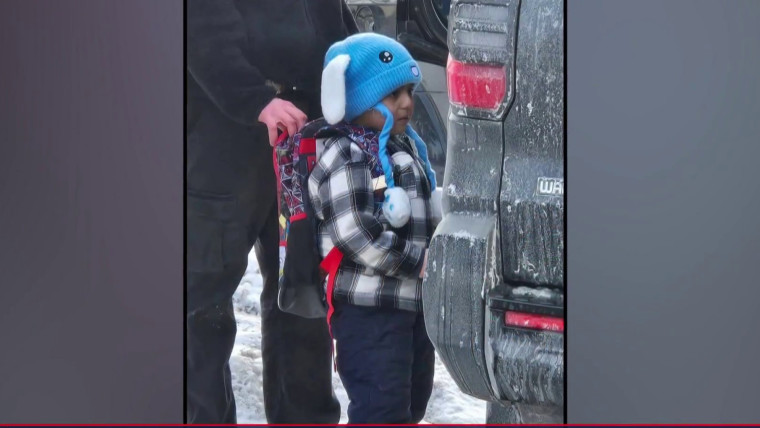

The center was thrust into the national spotlight last month after Immigration and Customs Enforcement took Liam Conejo Ramos, a 5-year-old boy, to the facility following his father’s arrest in Minneapolis — an encounter captured in a photograph showing the boy in a blue bunny hat as he was taken into federal custody.

The image ricocheted across the country, igniting outrage from lawmakers and the public. To many Americans, it was a sudden introduction to the harsh realities of ICE’s increasing reliance on family detention. But to Vargas and the lawyers who have spent months tracking conditions at Dilley, Liam’s fearful expression — and his father’s account of the child falling ill while detained — captured something painfully familiar.

“Liam is all the kids there,” said Becky Wolozin, a senior attorney at the National Center for Youth Law, which monitors conditions at the facility under a long-standing federal court settlement. “Just like Liam, we’ve had families tell us how their children have been horribly sick and throwing up repeatedly, refusing to eat and becoming despondent and listless.”

Those concerns have taken on new urgency in recent days after health officials confirmed two measles cases among people detained at Dilley. Advocates and medical experts warn that a highly contagious disease spreading inside a crowded facility housing young children — some already medically vulnerable — poses an acute public-health risk.

Lawyers representing families at Dilley say they have struggled to get clear answers from the Department of Homeland Security about the outbreak, including any steps being taken to limit its spread or verify whether children are vaccinated.

DHS didn’t answer questions from NBC News about conditions at Dilley. It has defended its use of family detention, saying in statements and legal filings that detainees are provided basic necessities and that officials work to ensure children and adults are safe.

Ryan Gustin, a spokesperson for CoreCivic, which has a contract to run the facility that’s expected to bring in $180 million annually, referred questions about Dilley to DHS and said in a statement that “the health and safety of those entrusted to our care” is the company’s top priority.

Since April, when the federal government resumed large-scale family detention as part of the Trump administration’s vow to dramatically escalate immigration arrests and deportations, an estimated 1,800 children had passed through Dilley as of December, according to figures provided by court-appointed monitors. About 345 children were being held there with parents that month, Wolozin said. Some families remain for a few weeks; others have been detained for more than six months.

Family detention was common during the Obama administration, and it expanded in President Donald Trump’s first term, before being largely halted under President Joe Biden. Unlike earlier iterations of family detention, many of the children now held at Dilley are U.S. residents, apprehended not at the border but at their homes, outside schools, in courthouses and during routine immigration check-ins.