GALLUP, N.M. — In 2020, as the Covid pandemic raged, the school district here thought it had found the perfect solution to help provide online schooling to its mostly Native American students when it hired a for-profit education company called Stride Inc.

Stride, a 25-year-old company also known as K12 Inc., is an industry leader in virtual education, serving over 220,000 students in 31 states last school year. It promised Gallup-McKinley County Schools (GMCS) it would provide teachers, laptops and internet hot spots for students who enrolled, in exchange for around $8,000 per pupil. The virtual school, New Mexico Destinations Career Academy, signed up roughly 1,000 students in the 2020-21 school year, a number that would quadruple over time.

Five years later, the district has ended its contract with Stride, a publicly traded corporation, and accused it of prioritizing profits at the expense of students. In interviews, court filings and government complaints, the district alleges Stride reported exaggerated student attendance counts to drive up revenue, neglected special education students and violated state law on student-teacher ratios. Graduation rates and math, reading and science scores among online students all declined, some dramatically, according to district data, while in-person rates improved or stayed the same.

In a complaint filed with the state Public Education Department in May, obtained by NBC News through a public records request, a key Stride employee alleged that top executives knew for at least two years that dozens of teachers were out of compliance with student ratio laws.

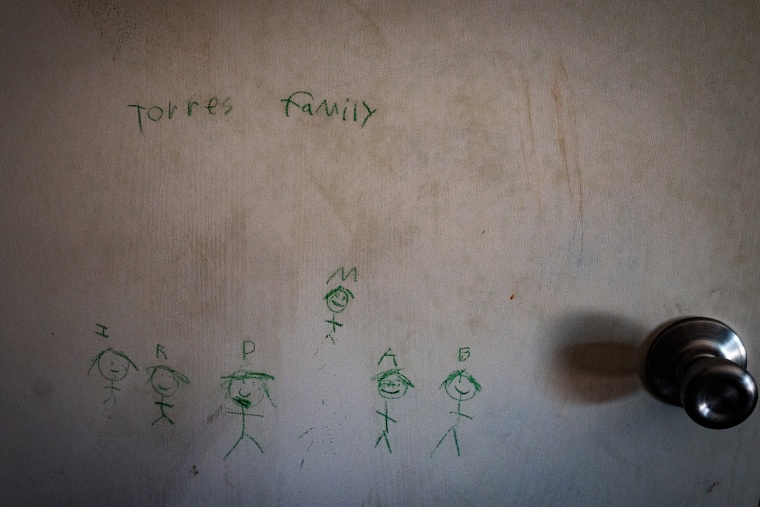

Mike Hyatt, the Gallup-McKinley superintendent, has blasted the company. “It was our students that were taken advantage of,” he said. “They’re the ones — whether they know it or not — that were harmed in this. And that just makes me sick inside that a company did this on our watch.”

Stride, a $6 billion company whose revenue has doubled over the past five years, is fighting back, with five lawsuits this year against the district that are still pending. It alleges that the district violated its contract with the company, along with laws governing open meetings for school boards, and it has refused to pay it for the past academic year.

Its attorney also lodged a conflict-of-interest complaint in April against Hyatt, prompting a state review of his educator’s license. Hyatt had applied for a job with Stride in December and been turned down in February. He said that there is no connection between the allegations and his rejection for the job and that the lawsuits are an attempt to distract from Stride’s problems.

A lawsuit the district filed against Stride in late August quotes the whistleblower, who said that on an April 8 Zoom call about the allegations, Peter Stewart, senior vice president of school development, said Stride should “attack first publicly.”

The state Public Education Department declined to comment on that whistleblower complaint, the allegations against Stride or the ongoing inquiry into Hyatt’s license. Stewart did not respond to a request for comment.

Stride also declined to address the whistleblower complaint. In response to questions, it defended its actions. “The situation with GMCS is highly unusual, and we believe the district’s actions have left us with no choice but to seek legal resolution to protect our students, staff and contractual obligations,” it said in a statement. “Stride is committed to fair and equitable business practices with our partner districts, and we deny the allegations made by GMCS.”