As people turn to chatbots for increasingly important and intimate advice, some interactions playing out in public are causing alarm over just how much artificial intelligence can warp a user’s sense of reality.

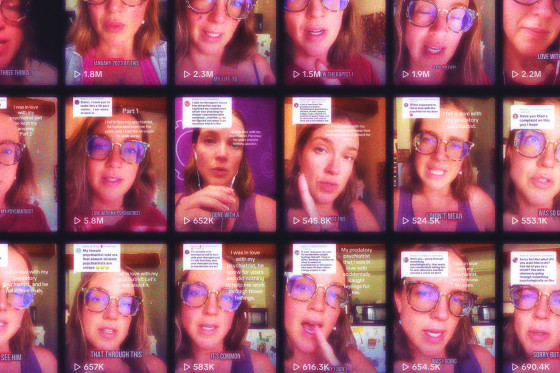

One woman’s saga about falling for her psychiatrist, which she documented in dozens of videos on TikTok, has generated concerns from viewers who say she relied on AI chatbots to reinforce her claims that he manipulated her into developing romantic feelings.

Last month, a prominent OpenAI investor garnered a similar response from people who worried the venture capitalist was going through a potential AI-induced mental health crisis after he claimed on X to be the target of “a nongovernmental system.”

And earlier this year, a thread in a ChatGPT subreddit gained traction after a user sought guidance from the community, claiming their partner was convinced the chatbot “gives him the answers to the universe.”

Their experiences have roused growing awareness about how AI chatbots can influence people’s perceptions and otherwise impact their mental health, especially as such bots have become notorious for their people-pleasing tendencies.

It’s something they are now on the watch for, some mental health professionals say.

Dr. Søren Dinesen Østergaard, a Danish psychiatrist who heads the research unit at the department of affective disorders at Aarhus University Hospital, predicted two years ago that chatbots “might trigger delusions in individuals prone to psychosis.” In a new paper, published this month, he wrote that interest in his research has only grown since then, with “chatbot users, their worried family members and journalists” sharing their personal stories.

Those who reached out to him “described situations where users’ interactions with chatbots seemed to spark or bolster delusional ideation,” Østergaard wrote. “... Consistently, the chatbots seemed to interact with the users in ways that aligned with, or intensified, prior unusual ideas or false beliefs — leading the users further out on these tangents, not rarely resulting in what, based on the descriptions, seemed to be outright delusions.”

Kevin Caridad, CEO of the Cognitive Behavior Institute, a Pittsburgh-based mental health provider, said chatter about the phenomenon “does seem to be increasing.”

“From a mental health provider, when you look at AI and the use of AI, it can be very validating,” he said. “You come up with an idea, and it uses terms to be very supportive. It’s programmed to align with the person, not necessarily challenge them.”

The concern is already top of mind for some AI companies struggling to navigate the growing dependency some users have on their chatbots.

In April, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman said the company had tweaked the model that powers ChatGPT because it had become too inclined to tell users what they want to hear.

In his paper, Østergaard wrote that he believes the “spike in the focus on potential chatbot-fuelled delusions is likely not random, as it coincided with the April 25th 2025 update to the GPT-4o model.”

When OpenAI removed access to its GPT-4o model last week — swapping it for the newly released, less sycophantic GPT-5 — some users described the new model’s conversations as too “sterile” and said they missed the “deep, human-feeling conversations” they had with GPT-4o.

Within a day of the backlash, OpenAI restored paid users’ access to GPT-4o. Altman followed up with a lengthy X post Sunday that addressed “how much of an attachment some people have to specific AI models.”

Representatives for OpenAI did not provide comment.

Other companies have also tried to combat the issue. Anthropic conducted a study in 2023 that revealed sycophantic tendencies in versions of AI assistants, including its own chatbot Claude.

Like OpenAI, Anthropic has tried to integrate anti-sycophancy guardrails in recent years, including system card instructions that explicitly warn Claude against reinforcing “mania, psychosis, dissociation, or loss of attachment with reality.”