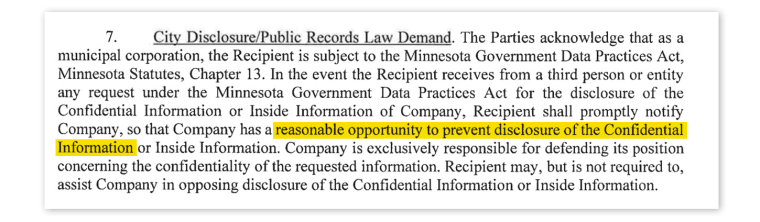

An NBC News review of over 30 data center proposals across 14 states found that in a majority of cases, local officials signed NDAs and worked with what appeared to be shell companies that can conceal visibility into the project developers. Five elected officials in different counties said the agreements barred them from sharing information with their constituents.

“That violates a very fundamental norm of democracy, which is that they are answerable first to the voters and to their constituents, not to some secret corporation that they’re cutting deals with in the back room,” said Pat Garofalo, the director of state and local policy at the American Economic Liberties Project, a nonprofit organization focused on economic equality.

Amazon, Microsoft, xAI, Google, Meta and Vantage Data Centers — six of the largest tech companies racing to build data centers across the country — all declined to or didn’t respond to questions about the use of NDAs in data center projects.

An information vacuum

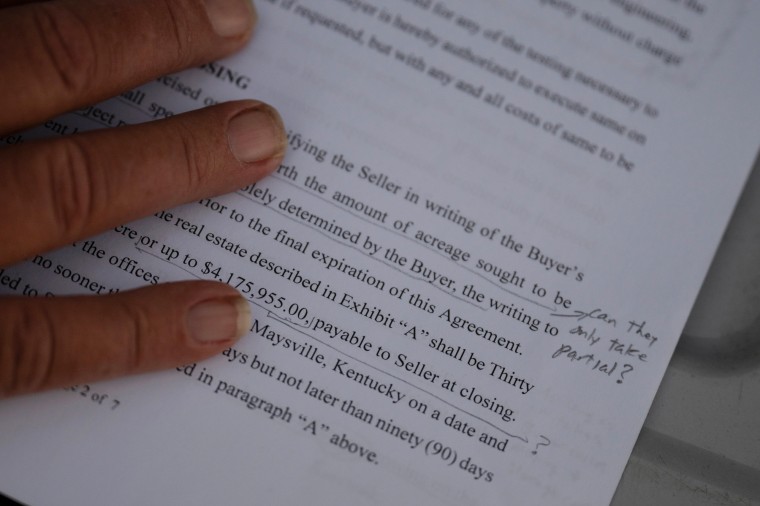

In Mason County, 20 residents, including Grosser, were offered deals to sell their land — thousands of acres in total — for significantly above market value, according to Tyler McHugh, director of the county’s industrial development authority, which is administering the deals. Eighteen of them signed property purchase contracts with the unknown company, agreeing to sell if the project proceeds.

The Huddleston family, whose relatives have lived on the same property for more than 150 years, said they signed a property purchase contract with the county’s industrial development authority for $60,000 per acre. When they learned from their neighbors that the land would be used for a data center, they asked McHugh for a legal release to absolve them of the contract and the confidentiality clause associated with it.

“The neighbors didn’t want to be sold out, and my mom and I agree with them,” Delsia Huddleston Bare said. “If it’s artificial intelligence, I don’t want it anywhere near me at all.”Huddleston said she was concerned about noise, pollution and groundwater contamination that could come with the project.

McHugh said he wishes he could be more transparent about what’s happening but worries controversy could scare away opportunity.

“If I could go get on a megaphone downtown and say everything I know about this project, I would,” McHugh said. “You know what’s going to happen if I do that? Then everybody in the county is going to put it on Facebook, they’re going to put it out there, and then it just becomes a huge mess. Companies don’t want to deal with that.”

“It’s just destroying trust in the government,” said Max Moran, the resident who started the Facebook group. “People just feel let down and kind of betrayed, because if you can’t ask what’s going on, then how can you trust anything they say?”